The Great Blur

On the Ill-Defined Playground of Big Tech's Foretellers

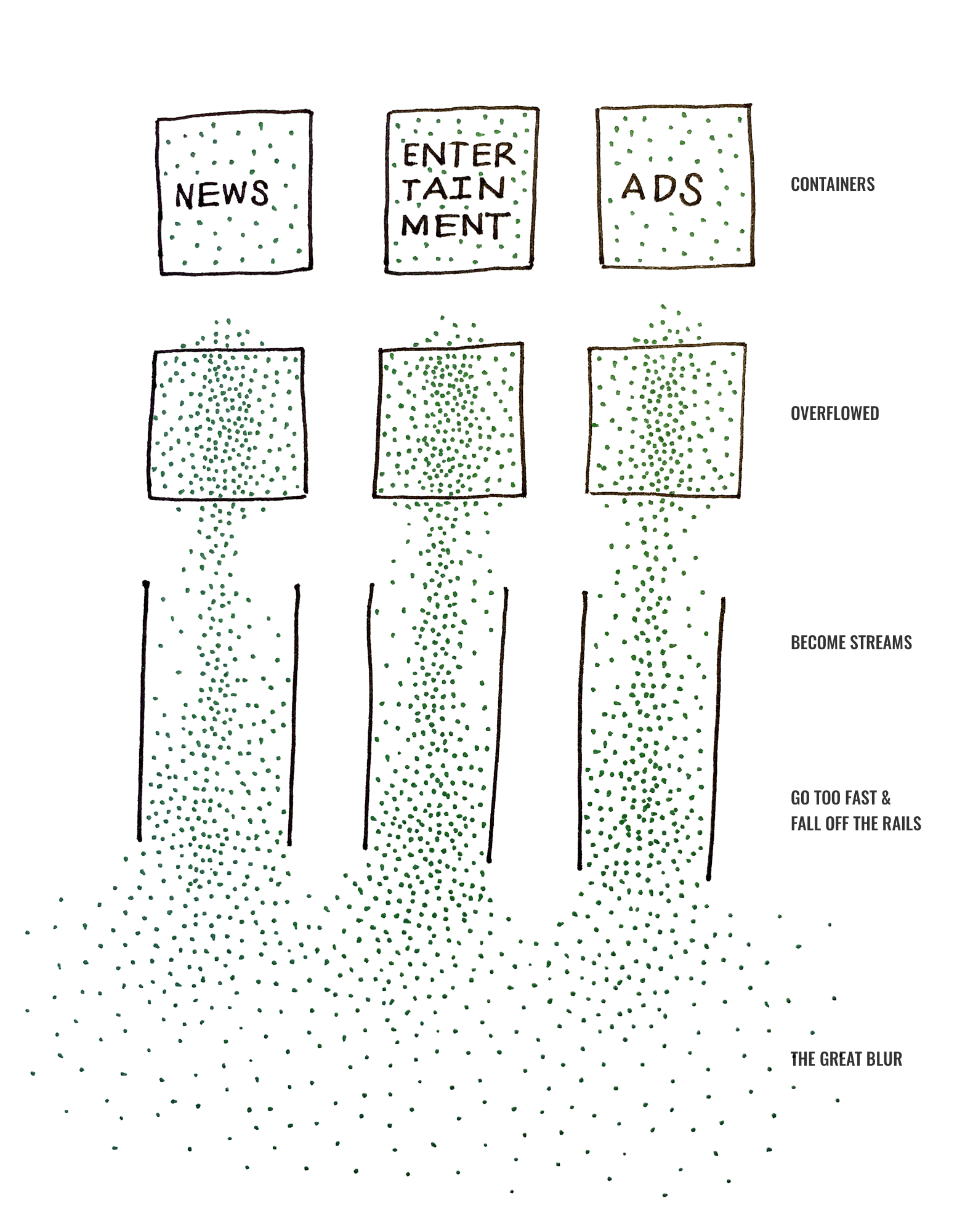

Originally, data was referred to with the lexicon of analog documents and files; data was collected and classified in labelled folders, categorized and archived in banker boxes. In today's digital world of information overload, the containers have overflowed and we talk about data in terms of endless feeds and infinite scrolls. Data is incessantly gushing out of every output.

“Things start to fall off the rails when you’re going really fast. [...] human animals, when dialed up past certain boundaries of speed, make poor choices.”

— Tristan Harris interviewed by Ezra Klein for Vox [1]

As a consequence of this new world of streams, the original containers are not clearly distinguishable from one another anymore. The lines between private and public, commerce and culture, work and life are blurred. Families install smart technologies throughout their homes, sharing continuous access to what has so far been beyond corporate reach. Lovers allow their devices into their beds, replacing intimacy with social feeds. Ads permeate our private channels. The always-on work culture enabled by the Web renders timezones irrelevant.

“Our political conversations are happening on an infrastructure built for viral advertising.”

— Renee DiResta at MozFest 2018 [2]

There is no way to fully grasp the breadth of the internet. We can't conceptually wrap our heads around its idea. Yet we are reliant on and constantly connected to its services in every aspect of our lives. Using the Internet is like reading a book with an infinite number of pages; a unique and personalized book that crafts a completely new narrative for you at every turn of a page. James Bridle, in his 2018 book New Dark Age, brings about this idea that we're entering an epoch similar to the dark ages where we are left with very little means before the increasing complexity of the world. Leaders of the tech industry are tapping into that vulnerability to further their own interests, deepening the divide between what's best for society and what's best for business.

The digital economy came about too quickly for politics and regulation to catch up with tech's Agile cadence. Tech companies have been operating their business according to the disrupter's mantra that it's easier to ask for forgiveness than for permission. Therefore, they acted in self-authorizing ways, taking advantage of laws that were not ready for digital services and social media. This lack of governance slowly allowed surveillance capitalism to set the rules. Surveillance capitalism is the commodification of human activity. It works by providing free services to billions of people in return for monitoring user behavior and capturing incredibly detailed data often without explicit consent. This is the business model of the internet.[3] In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff blames the phenomenon to "unilaterally [claim] human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data."

I think what's fundamentally wrong with this model is that the tech industry is constantly turning the world into information because it has become convinced it needs to predict the future. To stay one step ahead of the market, to predict upcoming social trends, to read the consumer's mind. This has become a huge market, estimated to be valued at USD $24 billion by 2025. [4] Artificial intelligence, prediction products, technology's ability to anticipate our every move. Companies are willing to pay so much to get a glimpse of what we're statistically inclined to do next.

By trying to monitor our behavior to better predict our future behavior, businesses are taking decisions that are more likely to alter the natural way of things. Blurring the lines between free will and corporate control.

“When man seeks to play God, nature has an uncomfortable way of reasserting itself.”

We're starting to play God, we're starting to refuse that we can't control everything, including the future. We're starting to deny the very things that make us human.

As the saying goes, you can't steer a parked car, but most importantly, steering a car that's hurrying down the fast lane is unpredictable and doesn't leave margin for error. Downshifting could allow us to better understand where we're going, make some u-turns, save on gas money, and enjoy the view while we're at it! We've created an unsustainable digital world for our brains and our planet. I believe we can reverse this process by slowing down[5] and thinking long-term[6].

[1] How technology is designed to bring out the worst in us | Tristan Harris interviewed by Ezra Klein for Vox

[2] The Internet's Original Sin | Renee DiResta at MozFest 2018

[3] "Surveillance Is the Business Model of the Internet" Bruce Schneier

[4] The global predictive analytics market size is expected to be valued at USD 23.9 billion by 2025, according to a study conducted by Grand View Research, Inc. on PRNewswire Dec. 2019

[5] Jack Cheng on the Slow Web Movement + Tariq Krim on Why We Need a Slow Web

[6] This The Long Now Foundation essay + Systems thinking on O’Reilly