Against Measuring

What if that which we scrutinize and compare isn't even a part of the world, but rather a mere representation of it?

Our Obsession With the Quantifiable

We seem to have become obsessed with measuring. In areas like work, technology and even our bodies, the quantifiable seems to be considered like more real than the qualitative. But quantifying everything creates a dependance on data. And that makes me want to question our desire to constantly observe the world. What if that which we scrutinize and compare isn't even a part of the world, but rather a mere representation of it? Are we stuck in a loop of levels of abstraction?

We Measure Time

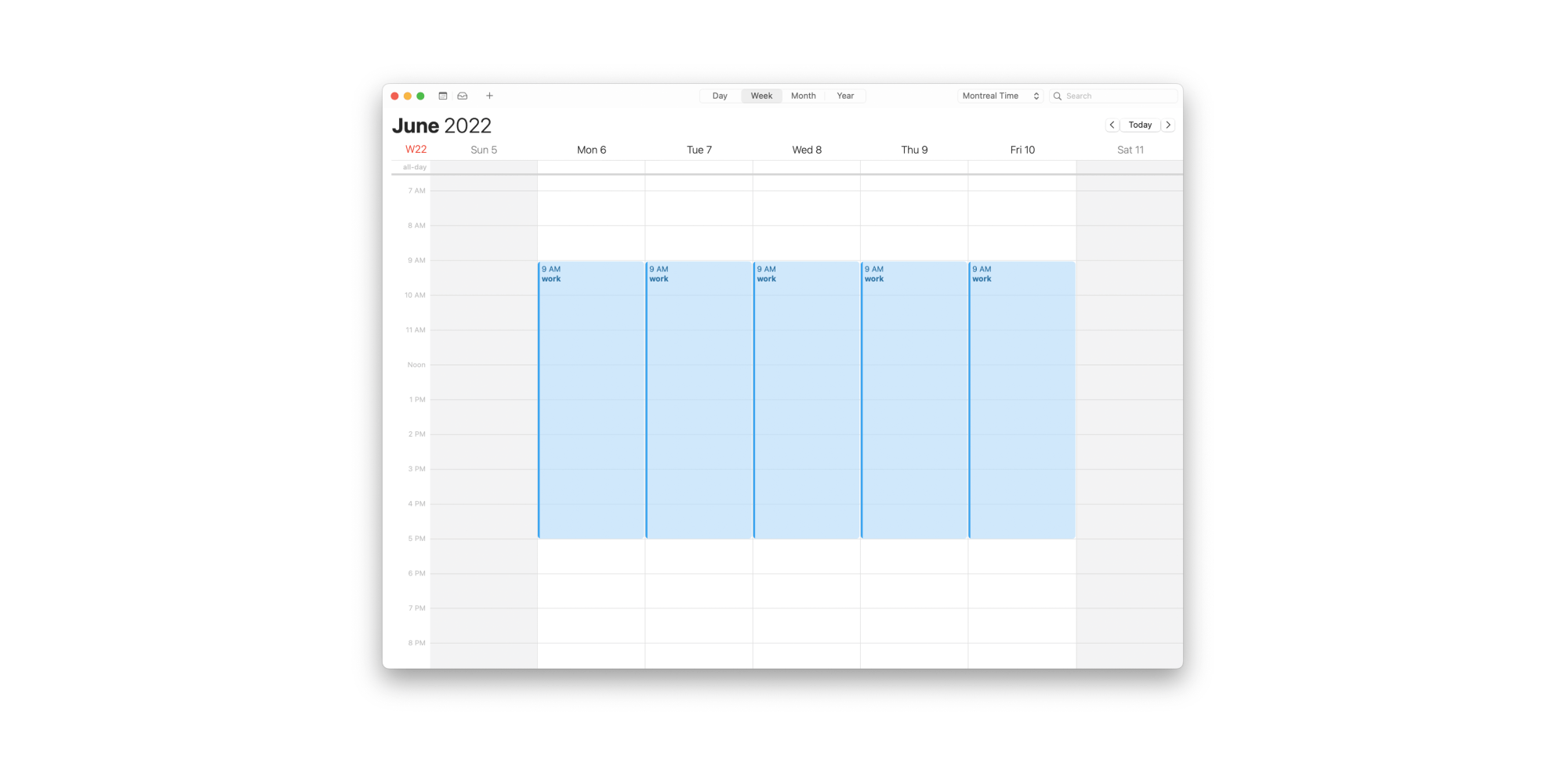

If you're a knowledge worker or in a creative field like me, you probably feel that productivity can't (or at least shouldn't) be measured in time alone. Measuring the hours of work only shows one dimension of productivity. It ignores the quality of the results or output, the level of focus one reached, the emotions one felt while working, the thoughts that came up during the process, it even ignores the very quantity of work.

Measuring requires to look only at the quantifiable. And the quantifiable offers a limited lens through which to look at work. The hours only confirm that, yes, I showed up during the daylight time of most days this week. Happy? Now on to the next one.

We Measure Behaviour

We see it in the tech industry a lot. We measure usage and engagement, time and money spent, clicks and scrolls. Almost everything that happens on the Internet gets tracked. We track so many metrics that we need to come up with imagined meanings for various combinations and series of them. Deltas, diffs, change over time, funnels. Then these measures become the only tangible proof that a company brings "value" to their customers. But perceived value, sentiment, appreciation are all super qualitative endpoints that can't quite fit in a string of digits.

I've written before about Big Tech's flawed business models and how when we start to play God, we are refusing what we cannot control (what doesn't fit neatly inside a database), and denying the very things that make us human.

We Measure Our Bodies

Isn't it fascinating how little we know of our bodies by default? That what makes up our very materiality is in fact so alien to us? Everything we know about our bodies and the interrelated systems that make it up, we learned in school. Our body is this strange autonomous vehicle that we just board without really understanding how and when to change the oil, or switch the tires. We don't even have to think about it and lungs breathe, hearts beat, and wounds heal. But also without us knowing, cancer grows, toxins build up, and blood clots. Can tech help?

Because of our lack of intuitive knowledge about our bodies, we have turned to technology to try and understand it. We measure what we eat, how fast we run, how many flights of stairs we climbed up. And then let the data tell us when to stand up, or when to take a deep breath, even when to look away from our screens. Might it be drawing us further away from ever intuitively feeling what's up with our bodies?

I wonder whether by relying so much on wearable technology, we'll come to a point where we let it tell us when something is wrong. Does more wearable tech mean we'll further enlarge the gap of understanding between our minds and bodies? We've created a new layer of abstraction with these metrics and data and measurements which, yes, (ironically) are more human-readable than looking at the veins on our wrist, but which ultimately increase the distance and reduce the possibility of intuitively knowing what's going on in our intricate machines.

The Issue With Measuring the Unmeasurable

What happens when we measure? In terms of the timeline of mankind, we haven’t been measuring for that long, but the technologies used to measure (pretty simple mathematical acts for a machine, really) have evolved exponentially. And what we do measure, we have extreme detail about. I’m serious, you don’t want to know what your Facebook advertising profile looks like, it’s more than creepy.

So what’s the problem with these measures being so specific? Well, first there’s the problem of context. When you gather abstracted numbers about things, people, and the things people do, the data is just that; numbers. And that data can’t live in a vacuum. By definition, to even have a measure, we need to detach a thing from its context to be left we nuance-free data. But without its context what does it really mean? Without the why and the how, what is a measure a measure of?

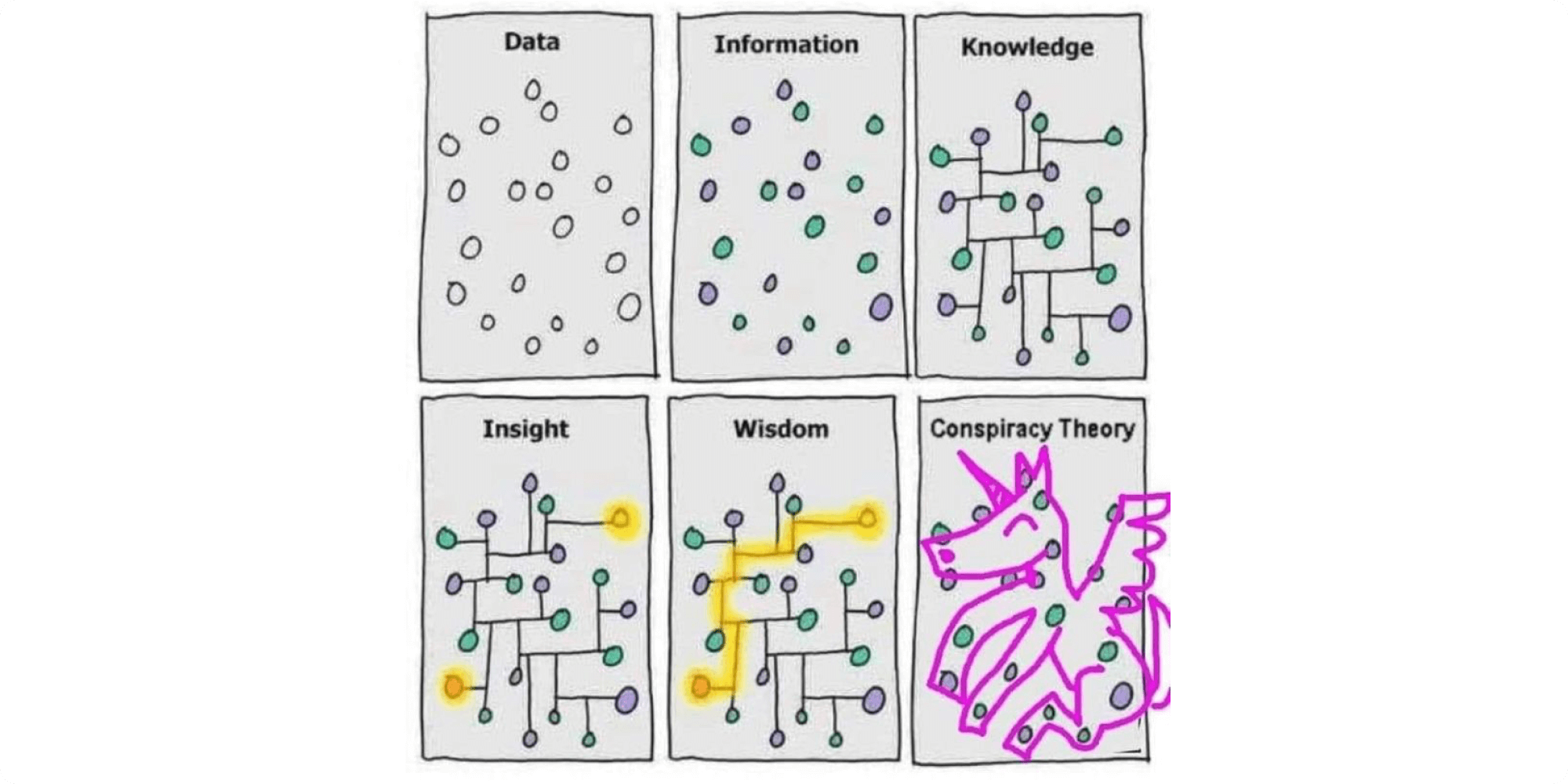

That's where we enter the vicious circle of levels of abstraction. We’re tracking and quantifying so much that we need to re-qualify in order to make sense of any of it. We extract nuance-free numbers from the narratives of their context and then rewrite new narratives around them to make them useful again, to tell stories and reveal actionable insights.

The New Commodity

When we think about it, whole industries are now based in measures. Advertising, marketing, behavioural science (all science, really), the stock market, investments. And it is through industry, as it got more and more data-centric, that we started seeing those qualitative trends like storytelling, human-centred everything, coming in to balance it out.

Through this looping of levels of abstraction, we've managed to make it work; data as the new oil. We’re seeing it in our cities, in our work, in our homes, on our fingers. But what even is data? It’s not quite information because as I explained earlier, a datapoint is not informative on its own. And we’re even farther from calling it knowledge or even wisdom. What is data then? Data is the new global commodity. It's raw material with monetary value and you need a whole lot of it for it to be even remotely valuable. So we measure and we measure and gather data and data and then what?

Why We Measure

A big part of the reason for there being measurement in the first place is comparison. Comparing to a benchmark, a national average. Comparing between two current things; comparing your performance at the gym to that of your friend. And comparison between the past, the present and the future. We measure to see how things stand in relation to others.

With these comparisons, we get to prove value, quantify progress, make sense of trends and decipher signals. Ultimately, what gets measured acts as a basis from which we can extrapolate predictions. We infuse that knowledge (intelligence, insight, pick your favourite buzzword) into decisions that shape the future.

At their core, measures are nothing but a record of the past. And then we consider them as the new gold and predict future behaviour, future business, future opportunities. But these predictions never really go farther than repeating that which has already been occurring.

«Data always looks backward, meaning historical prejudice is frozen into a training corpus.»

—Cennydd Bowles, Future Ethics

We, as a society, have developed the reflex to look exclusively at the past in order to head into the future. If that’s not the most reductionist way to limit potential, I don’t know what is.

Data is (mostly) bad and measuring is restrictive. Our obsession with data and measuring limits the future’s potential to merely reproduce what we already know tends to happen. How might we go beyond reproducing? How might we tame our obsession with measuring? What’s a societally healthier way to observe the world that doesn’t involve siloed numbers in a database?

Context, Nuance & Representation

We’re tangled in this mess of measuring concrete things, imagining intangible value for them, even though it all comes down to very concrete dollars. The imagining of quality, though, ends up working, because like money, it’s an abstract thing until everyone agrees to believe in it. Then it becomes tangible.

"Money isn’t a material reality – it is a psychological construct. It works by converting matter into mind. [...] Whereas religion asks us to believe in something, money asks us to believe that other people believe in something."

—Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens

It’s a matter of trust. We all trust that time is money so work gets reduced to measuring hours. We all trust that the number of daily active users means the number of happy users. We all trust that our bodies need 8 hours of sleep so we let our phones tell us when to start winding down.

But if we were to really examine that data, and look into the context around each data point, we would very quickly see how much nuance we’re losing. Or rather how much nuance we’re actively choosing to ignore.

I believe it all comes down to the fact that the important things in life can’t be measured. But unfortunately, the modern digital world has grown so dependant on data, that the act of measuring itself has become important. Measuring is running the global economy right now and that’s worrisome. We’re giving more and more importance to measuring which by definition excludes the important things in life such as creativity, sentiment, intuition. What does that say about capitalism? What does that say about us as a society?

To me, it's really a matter of challenging our obsession with observing the world.

As the human race, can we really not observe the world? What would we base our decisions on? (But then why do we need to make decisions? Kidding I won’t go there but... right?) What’s another way of observing the world than measuring every square millimeter of it? Poor world. It constantly gets scrutinized, compared, analyzed, turned into actionable insights (remember those buzzwords?).

We’re taking the vibrant richness of the world, the incalculable diversity and detail of the people in it and constantly abstracting its activity into dumb, lifeless numbers. And for what? What if the world wasn’t measurable? What if that which ends up being measured isn’t even a part of the world? It is only our perception of it, a mere representation of its essence. Yet we measure that representation and bring it to yet another level of abstraction in order to decide on concrete actions that’ll impact the even more abstract future.

How could we measure the world for what it truly is? Beautiful and complex and painful and dirty and weird and illuminating and horrific. How can we measure beauty? Why would we measure pain? Can we quantify weirdness? Who would want to measure horror? Can illumination really be represented outside of art perhaps? How might we capture filth and extasy and identity and memory? But most importantly, why would we? Why would we need more than to experience them?